For centuries, Chaco Canyon was a gathering place where ancestral Puebloan peoples came together to make their world a better place. At the heart of the ancient civilization’s genius are the complex and intricate relationships between its grand architecture, global commerce, ceremonies and their link to solar and lunar cycles.

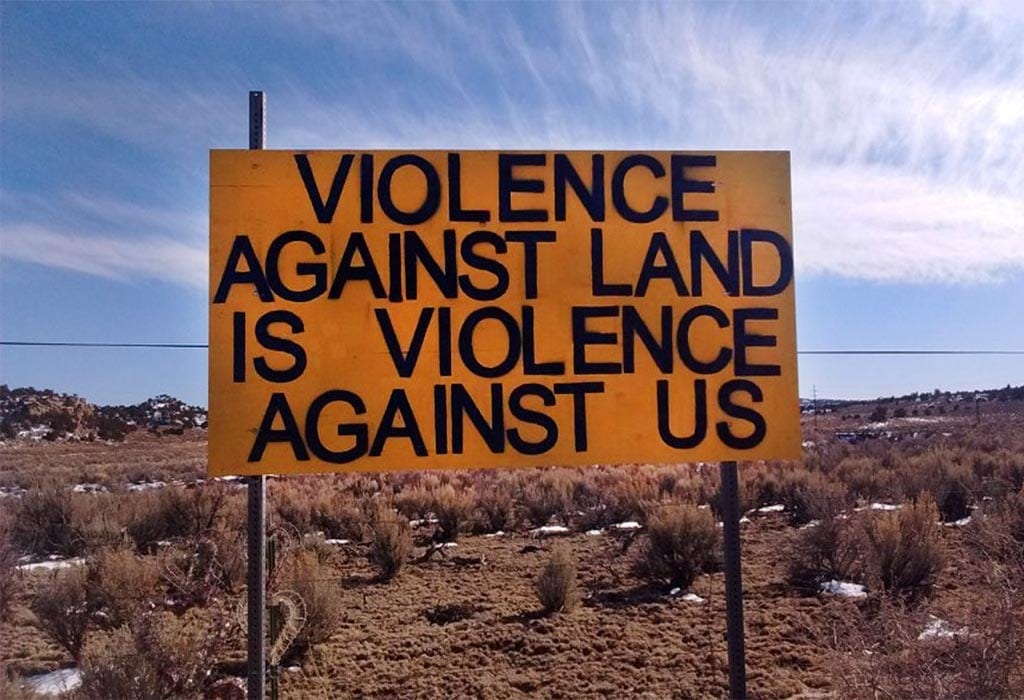

Now people are, once again, coming together again to defend Greater Chaco, and the genius of this modern gathering of people lies at the intersection of climate justice and social justice.

Earlier this month, Interior Secretary Ryan Zinke unexpectedly halted the proposed sale of 4,434 acres of public minerals in the Greater Chaco region to the oil and gas industry. But make no mistake, this is only a momentary reprieve.

Zinke’s decision came as a result of unprecedented opposition from Pueblo and Navajo leaders, New Mexico’s congressional delegation, environmental groups and countless citizen activists opposed to the continued desecration of sacred lands. Delaying the sale means the Bureau of Land Management will complete an extensive cultural report, which will be used to inform decisions about whether to allow drilling in the area.

Reprieve is not victory.

For the real solutions that implement a new vision and lasting solutions for the Greater Chaco landscape and all the cultures, and people who are connected deeply to it, we need a coalition of those who care about protecting this treasure, as well as congressional leadership from Sens. Tom Udall and Martin Heinrich.

It’s time for federal legislation to be crafted that addresses historic injustices and advances a new energy economy. We believe four core principles should guide legislation to protect Greater Chaco’s ancient cultures, current inhabitants, public lands and climate.

First, we must bring an end to the era of expanding fossil fuel extraction. Ninety-one percent of available public land already is leased for energy extraction. Legislation must permanently withdraw and protect Greater Chaco lands not already privatized by the oil and gas industry.

Second, we must invest significant federal dollars to provide communities in Greater Chaco better economic opportunities not based on the boom-and-bust nature of fossil fuels. Investing in clean energy development and eco-cultural recreation is key to the long-term stability and security for the region. Both could remedy longstanding climate injustices on Navajo land.

Third, we must protect a much larger landscape. Greater Chaco is a patchwork of protected ruins and other culturally significant locations. Because of the diversity of tribes responsible for protecting Chaco culture, any new designations must explicitly provide for joint-management authorities to all related tribal entities.

Fourth, we must repatriate certain public lands to Native peoples. Restore justice for Navajo communities and all indigenous peoples for whom Greater Chaco is spiritually and culturally important. A bill introduced by Sen. Heinrich largely addresses this issue.

Already, real and lasting damage to Greater Chaco’s cultural heritage has occurred because of fracking. Tribal elders and archaeologists speak of hallowed ground outside the park itself that is now surrounded by drill rigs, pump jacks and pipelines. This sacred land now has the feeling of an industrial park.

Unfortunately, we can’t escape this reality. But we can let it inform our future.

Zinke’s lease decision provides a rare opportunity to turn reprieve into revolution, a revolution that recognizes that Chaco’s treasures were only partially protected when Teddy Roosevelt designated Chaco Canyon as a national monument 111 years ago March 11. A revolution built on Chaco’s ancient wisdom that our right relationship to the sun is critical to our survival.

I implore you to raise your voice and demand this sacred ground is protected now and for future generations.