The United States Forest Service manages 193 million acres of national forests, most of which are in the western U.S. These forests are the source for half of the West’s water, provide habitat to thousands of wildlife species (including threatened and endangered species), and offer recreational and mental wellness benefits to millions of Americans.

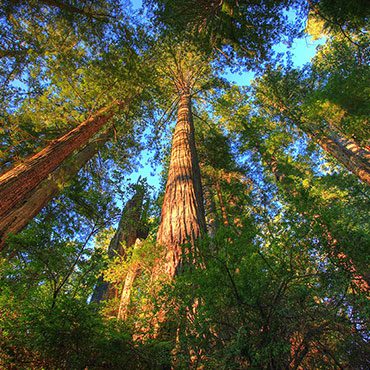

Old-growth forest. Photo by Bob Wick

It’s hard to overstate just how important our national forests are to our lives. Yet is the Forest Service managing these irreplaceable forests to the benefit of all of us, as they are supposed to? A recent Forest Service report to Congress provides a blueprint of how the agency could increase logging to meet arbitrary, non-science based timber production goals.

The mechanisms proposed by the Forest Service to meet these “Timber Targets” include cutting public involvement in decision-making and oversight of agency action, to make it easier to cut more trees, including from forests that are key to combating climate change.

What’s in the report?

In 2021, the Forest Service sold 2.84 billion board feet of timber from our national forests. In 2022, that increased to 2.94 billion board feet and in 2023 to 3.08 billion board feet. To put this in perspective, 3.08 billion board feet of timber would fill over 1.25 million log trucks. Even though this level of timber volume sold is “higher than any period in the previous few decades,” this “Timber Target report” to Congress indicates the Forest Service wants to log even more trees from our national forests.

The document outlines how the agency can increase logging in our national forests by at least 25 percent above current levels, to four billion board feet each year! The last time the Forest Service sold that much timber from our national forests was 1993, the year the agency started developing the Northwest Forest Plan to address habitat loss for the northern spotted owl caused by—that’s right—overlogging. That level of logging was not sustainable then and it isn’t sustainable now, especially in light of what we know now about the importance of protecting mature and old-growth forests to mitigate the effects of climate change. Nevertheless, the Forest Service wants to turn the clock back and actually spells out just how it wants to do that.

Cutting the public out

In order to increase timber volume output to four billion board feet each year, the Forest Service says it needs “new authorities” for “expediting environmental analysis.”

Translation? The Forest Service wants to make it harder for the public to comment on and challenge timber sales in court.

The agency is quite explicit about this, pointing to litigation in Montana and Idaho that it claims (without evidence) is “delaying timber-producing projects” and in some cases “shut[ting] down timber harvesting operations and offerings of new sales.”

The remedy, according to the Forest Service, is not to stop proposing ecologically damaging timber sales that violate the law, but rather to ask Congress for “legislative fixes” that make it harder, if not impossible, to challenge ecologically damaging timber sales in court. Streamlining environmental reviews and limiting public input, the Forest Service says, “will help increase timber volume sold.”

Rebuilding roads at the expense of restoring watersheds and wildlife habitat

Rewilding unneeded forest roads restores secure habitat for wildlife such as bears and elk. Photo of Olympic National Forest.

According to the report, another impediment to increased logging is the Forest Service’s massive, deteriorating road system (currently 367,000 miles). The agency says that its backlog on road maintenance (currently $5.3 billion) directly impacts the technical and economic feasibility of timber sales. In other words, the Forest Service is telling Congress to give it more money to reconstruct its road system so that more of our national forests are accessible for logging.

The problem is the Forest Service acknowledged over 20 years ago that the size of its road system is not ecologically sustainable and must be significantly reduced. As a result, the Forest Service implemented its Travel Management Rule in order to “minimize and begin to reverse the adverse ecological impacts from roads” on national forests. Importantly, this included identifying and “aggressively decommissioning unneeded roads” to restore degraded watersheds and wildlife habitat.

Unfortunately, in the last two decades, the Forest Service has only decreased its sprawling road system by 3.5 percent (~ 13,000 miles). Much more work needs to be done to achieve the objectives of the Travel Management Rule. Instead of asking Congress for funding to rebuild its road system to facilitate more logging, that funding should be directed towards decommissioning roads through programs like the Legacy Roads and Trails Remediation Program, which prioritizes protecting drinking water and wildlife habitat. That would meet the objectives of the Travel Management Rule while also supporting high-paying jobs in restoration.

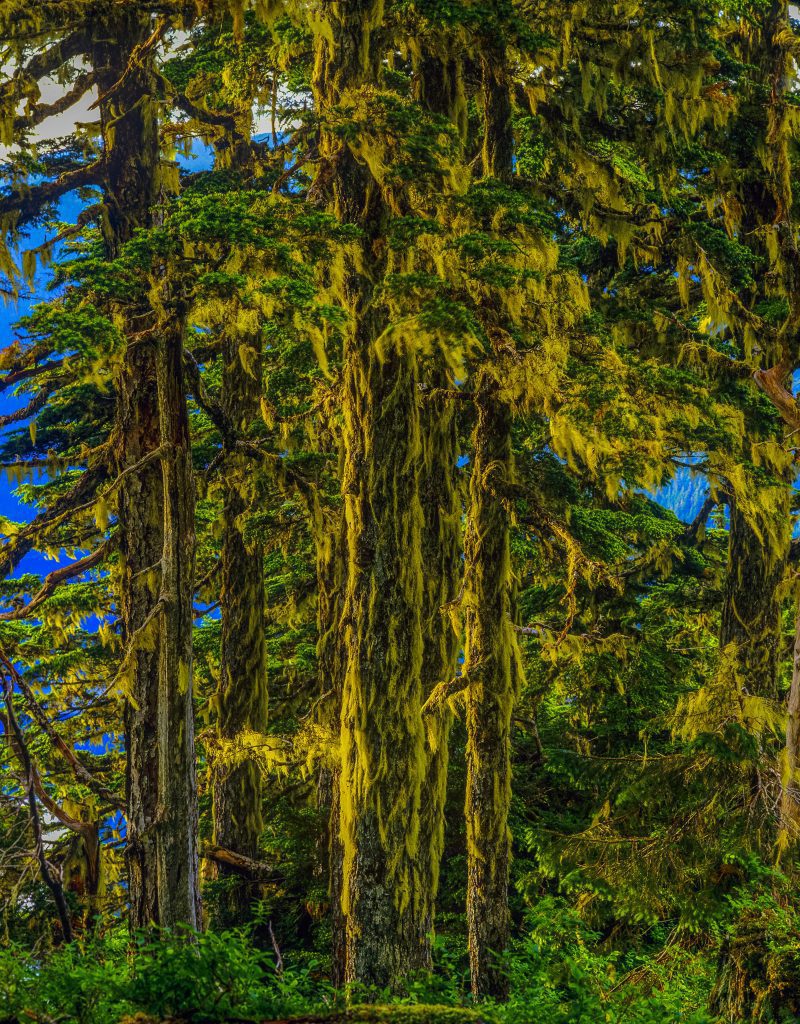

Seeing old-growth as the problem rather than a climate solution

Next, the Forest Service blames the Biden administration’s policy for protecting old-growth forests in Alaska as a reason it cannot currently increase timber volume levels. That policy, the Southeast Alaska Sustainability Strategy, is intended to end large-scale old-growth timber sales in the Tongass National Forest and help mitigate the impacts of climate change. To the Forest Service, however, it is just another roadblock to increased logging.

Western hemlock and lichen on the Tongass National Forest. Photo by Howie Garber.

This raises significant concerns since the Forest Service is currently in the process of developing standards ostensibly to protect old-growth forests on all national forests. But how can the public have any confidence that the Forest Service will implement strong old-growth protections nationwide when it blames existing policies to protect old-growth forests in Alaska as a barrier to increased logging? The current old-growth rulemaking cannot be another sham, publicly expressing interest in the conservation of old growth, while behind the scenes the agency plots another course of action that puts a target on old-growth forests. We need to be vigilant.

Targeting the Pacific Northwest

One of the most alarming parts of what the Forest Service reported to Congress is the fact that it identifies the Pacific Northwest as one of the regions of the country that “should have the greatest increase in total timber volume sold.” This places the agency at odds with research identifying these “high-carbon-priority forests” as critical for mitigating climate change, not to mention providing critical habitat for threatened and endangered species. Moreover, as the Forest Service recently announced that it will amend the Northwest Forest Plan, one must question whether some of the measures that have been in place for the last 30 years to protect imperiled species will be loosened to facilitate increased logging across national forests in Oregon and Washington to meet arbitrary goals. As the Forest Plan amendment process unfolds, Guardians will ensure that proposed timber targets do not erode essential watershed and wildlife habitat protections.

Concern about the Forest Service’s timber targets has already prompted at least one lawsuit. In February 2024, the Southern Environmental Law Center (SELC) sued the Forest Service claiming the agency failed to consider the carbon impacts of setting arbitrary timber production targets that agency officials are then expected to meet. Indeed, internal Forest Service emails indicate that agency personnel are under immense pressure to find ways to reach annual timber production targets and that awards are given out each year to staff who hit those targets.

Such perverse incentives are a stark reminder that timber production remains the overarching priority for the Forest Service while all other values, like wildlife or climate mitigation, are a distant second. As the Forest Service seeks to push timber production levels even higher, those of us who care about our national forests must be ready to speak up and tell the agency and lawmakers that we cannot turn the clock back to a time when unsustainable logging pushed species like the northern spotted owl to the brink of extinction. Instead, the Forest Service must redirect its focus toward restoring fragmented watersheds and wildlife habitat and protecting and restoring old-growth forests that provide our best nature-based defense to climate change.

Olympic National Forest.