From the exquisite red rock ravines of Grand Canyon National Park, to the wildflower-strewn meadows of Carrizo Plain National Monument, to the roaring waters of the Rio Grande Wild and Scenic River, the West abounds with public lands. Americans—and tourists from around the world—seek out these awe-inspiring places to hike, marvel at wildlife, kayak, hunt, fish, and much more. But what exactly are public lands? Who’s in charge of them? And how does a national park differ from a national monument or a Wilderness Area? Read on to find out.

Photo credit: NPS

What are public lands?

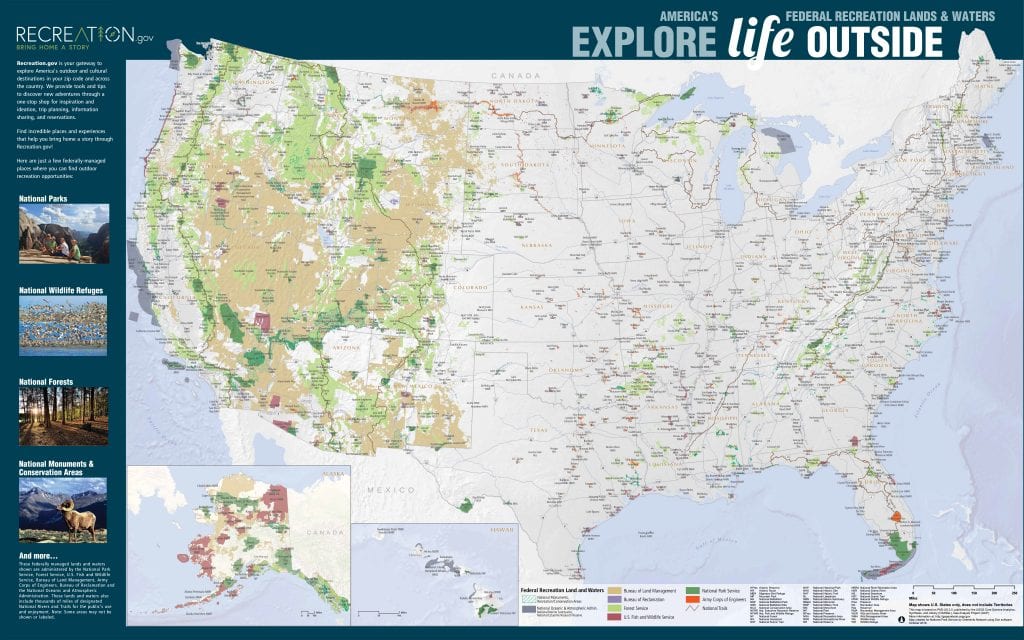

There are approximately 640 million acres of public lands in the United States—lands that are managed and administered by the federal government on behalf of the owners, the American people.[*] Public lands comprise about 28 percent of the more than 2.3 billion acres of U.S. land. These lands are managed for many different purposes under many different designations, primarily by four federal agencies.

Which federal agencies manage public land?

About 95 percent of all public lands are administered by one of the four primary federal land management agencies.[†]

- The Bureau of Land Management, within the Department of Interior, manages more than 248 million acres of public lands, more than any other agency. Nearly all BLM-administered lands are located in the West or Alaska.

- The Forest Service, within the Department of Agriculture, manages almost 193 million acres of national forest and national grassland, second-most among the federal land management agencies. While most national forest and grassland is in the West, the Forest Service manages about half of all public lands in the East.

- The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, an Interior agency, administers the almost 90 million acres of public lands that constitute the national wildlife refuge system.

- The National Park Service, also within Interior, administers about 80 million acres of public lands with various management designations, including national parks, national monuments (BLM and the Forest Service also manage national monuments), national historic sites and national battlefields.

What are the different public lands management designations?

There are numerous designations for managing public lands. Some of the designations can only come from Congress; others are identified by the agencies. Designations can overlap—public land can be designated a wilderness area inside a national park, for example. Among the most important designations are:

- Wilderness Areas – Only Congress can designate “capital W” wilderness areas. The Wilderness Act of 1964 defines wilderness as “an area where the earth and its community of life are untrammeled by man, where man himself is a visitor who does not remain.” It is usually considered the most protective designation for public lands, with the land managed to preserve its natural, untrammeled condition. All four federal land management agencies administer wilderness areas according to the requirements of the Act. There are more than 750 wilderness areas across the U.S. protecting more than 100 million acres of public lands. Wilderness areas, along with wilderness study areas and inventoried roadless areas, are wildlife strongholds, especially for species such as the grizzly bear that require large, varied, undisturbed habitats. These areas will also serve as essential climate change refugia in the coming years as the impacts of global warming become more severe.

- Wilderness Study Areas—WSAs are BLM-administered lands that the agency has inventoried and found to have the characteristics of wilderness but have not been formally designated by Congress. BLM is required by law to protect the wilderness values of WSAs until Congress decides whether to designate them as wilderness, but this does not mean they need be managed exactly the same as wilderness areas. Some WSAs are managed to permit off-road vehicle travel, for example. BLM manages more than 12 million acres of public lands as WSAs.

- Inventoried Roadless Areas—The Forest Service also administers lands that have wilderness characteristics—namely, a lack of roads—but have not been designated by Congress. IRAs are administered under a set of 2001 Forest Service regulations collectively known as the Roadless Rule. The Rule is meant to limit road-building, but does not prohibit development within IRAs. More than 58 million acres of national forest are protected as IRAs.

- National Parks—National parks are designated to conserve and provide for the enjoyment of the country’s scenic, natural and historic wonders and their wildlife. Although national parks contain some of the country’s most spectacular wilderness, outside those areas the national parks are managed for public use and enjoyment as well as for conservation, allowing for greater human impacts on the land.

- National Monuments— National monuments protect nationally significant prehistoric indigenous sites, archeological sites, and historical and geological sites. National monuments are designated by Congress, or, more frequently, by the president under authority of the Antiquities Act. The National Park Service manages or co-manages the majority of the national monuments (89 of the 130 total), with the BLM, Forest Service and Fish and Wildlife Service managing smaller numbers of monuments.[‡]

- Wild and Scenic Rivers—Most wild and scenic river designations come from Congress, though the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act provides for the Secretary of Interior to designate a river under limited conditions upon a state governor’s request. The Act provides for three separate river designations: wild, scenic and recreational. Wild rivers are undammed and not accessible by road. Scenic rivers are free of impoundments, have largely undeveloped shorelines, but may be accessed by road in places. Recreational rivers may have impoundments, can be reached by road and have development on their shores, but nonetheless have outstanding recreational values. Once a river is designated it must be managed to protect and enhance the values of its classification. All four federal land management agencies administer wild and scenic rivers.

What is the legal basis for public lands in the United States?

All federal public lands, as well as all private and state-owned land in this country, were seized from Indigenous peoples by either European or Euro-American colonizers that used the Doctrine of Discovery to justify the theft. The doctrine, rooted in a series of 15th-century papal edicts, claimed that Native inhabitants, because they were not Christian, did not and could not hold title to the land on which they lived. Rather, title to a piece of land was said to be held by the first European nation to “discover” it. In 1792, Thomas Jefferson, as Secretary of State, extended the Doctrine of Discovery claim to the United States government in 1792. The doctrine was established as the law of the land by Chief Justice John Marshall in the 1823 Supreme Court case Johnson v. M’Intosh and has served as the legal basis for invalidating and denying Indigenous possession of lands in the United State ever since.

The first “public lands” in this country were established in 1781 when New York surrendered to the U.S. government (then a confederation) its claim to unsettled lands westward to the Mississippi River. The other states eventually followed suit and the lands between the Mississippi River and the western boundary of the Thirteen Colonies were classified as public domain lands. Later, as the United States “acquired” new territories, the unsettled portions of those territories were also categorized as public domain lands, owned in common by the American people.

The U.S. Constitution, ratified in 1788, addressed the relationship of the federal government to the lands within its borders. The Constitution’s Property Clause conferred on Congress sole authority to manage and control all territories and other property owned by the United States.[§] The Supreme Court has consistently interpreted the clause to grant Congress’ exclusive authority to decide on whether or not to dispose of public lands and how public lands should be managed.

Over the years, Congress passed laws providing for the divestiture of a significant share of the nation’s public domain lands.[**] The most well-known of these laws is the Homestead Act of 1862, which allowed any adult citizen, or intended citizen, to take title to a 160-acre plot of surveyed government land so long as the claimant improved the plot by cultivating the land and building a dwelling.[††]

As new states entered the Union, Congress gave each a share of the public domain lands inside its borders. In many states, sections 16 and 36 of each township were given away with the provision that revenue generated from those sections would be dedicated to funding the state’s public education. The federal laws admitting new states, known as state enabling acts, required that states give up any and all claims to public domain lands inside their borders as a condition of admission.

The public lands left today were either never divested under the numerous public lands divestiture laws and state enabling acts, or were reacquired at a later date from the states or private parties to promote national values. Some National Forest lands, for example, were re-acquired after passing into private hands to protect water sources.

But what about the argument that public lands are rightfully the property of individual states, not the United States?

The Constitution’s Property Clause, in conjunction with the state enabling acts, thoroughly invalidates these arguments from Cliven Bundy and anti-public lands western politicians. Bundy’s self-serving claim that federal control of public lands is illegitimate is nothing more than an idiosyncratic interpretation of the Constitution based on a rancher neighbor’s reading of Mormon scripture. It has no basis in law.

Utah and other states that have demanded the federal government to turn over public lands are on only slightly firmer legal ground. Although no Supreme Court case has definitively addressed the question of whether the United States may retain public lands in federal ownership indefinitely, the Court has stated that the authority of the United States under the Property Clause has “no limitations,” and that the United States has “the absolute right to prescribe the times, the conditions, and the mode of transferring this property.”[‡‡] The Supreme Court has also found that “the government has, with respect to its own lands, the rights of an ordinary proprietor, to maintain its possession,” including that it “may sell or withhold them from sale.”[§§]

Despite this clear language from the Supreme Court, the Utah legislature underwrote a 2015 legal analysis suggesting there are several viable legal avenues to bringing a lawsuit demanding that public lands be turned over to the states. These arguments expand and extend existing legal principles regarding states’ Constitutional rights, such as equal footing and equal sovereignty, to claim that federal retention of public lands leaves western states at such a political and/or economic disadvantage as to violate the Constitution. However, a 2016 Conference of Western Attorneys General (WAG) report found scant legal support for these arguments.

Several western states have argued the state enabling acts require U.S. divestment of public lands. Because the individual enabling acts contain facts specific to each state’s admission, the WAG report did not address this argument. But most other analyses have found that enabling acts undercut, rather than support, this position. This is because nearly all of them—including those of the most virulent anti-public lands states, such as Utah and Nevada—contain a provision in which the state disclaims any right or title to unappropriated public lands.

[*] This discussion is limited to public onshore surface lands. The federal government also manages energy and mineral resources located below ground and offshore. These include about 700 million onshore acres of federal subsurface mineral estate and about 1.7 billion offshore acres in federal waters on the U.S. outer continental shelf.

[†] The Department of Defense administers about 11 million acres in military bases, training ranges, and other sites. Other federal agencies, including the Bureau of Reclamation, the Postal Service, NASA and the Energy Department administer the rest.

[‡] The Commerce Department’s National Oceanic and Atmospheric Association (NOAA) co-manages five marine national monuments with the Fish and Wildlife Service.

[§] Article 4, Section 3, Clause 2: The Congress shall have Power to dispose of and make all needful Rules and Regulations respecting the Territory or other Property belonging to the United States; and nothing in this Constitution shall be so construed as to Prejudice any Claims of the United States, or of any particular State.

[**] Congress has also re-acquired some of the public domain lands that had been divested, including portions of the National Forest system.

[††] The passage of the Federal Land Policy and Management Act of 1976 (FLPMA) repealed the Homestead Act and established that public lands were to be retained in public ownership.

[‡‡] Gibson v. Chouteau, 80 U.S. (13 Wall.) 92, 99 (1871).

[§§] Camfield v. United States, 167 U.S. 518, 524 (1897).