My favorite time to visit the Gila is in July, after the monsoons have started. The plants are shooting up new green growth, the air is full of delicious smells, birdsong, and optimism, and slick mud patches capture clear tracks, revealing whom you just missed in the woods.

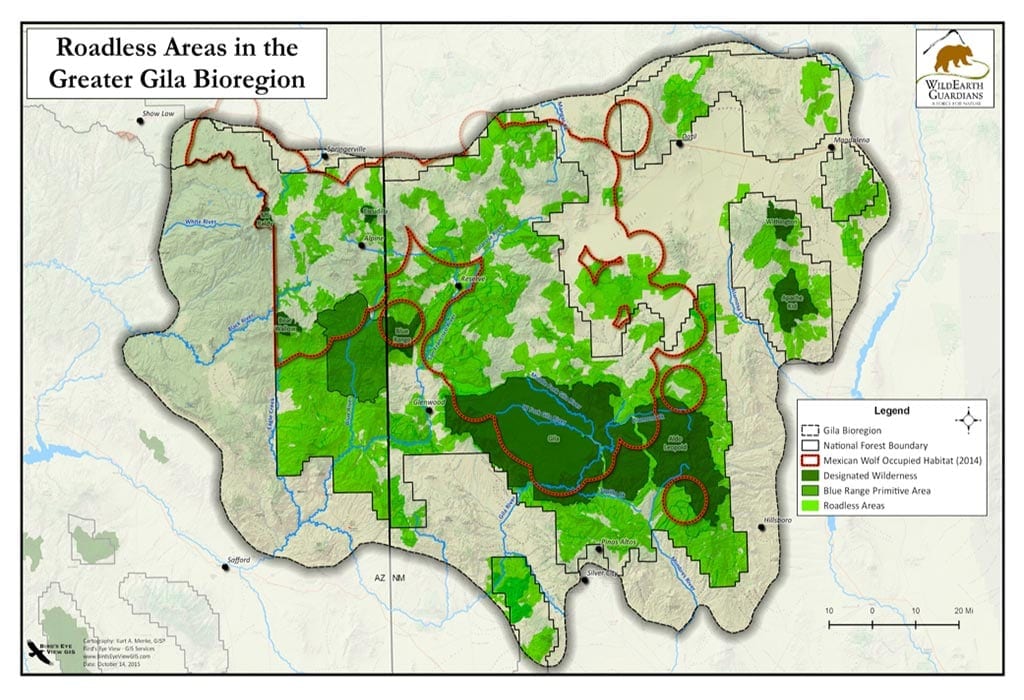

Location of the Gila.

Last week, Guardians’ Conservation Director, Sarah McMillan, Wild Places Program Director, Judi Brawer, and I spent four days circumnavigating the Gila National Forest and meeting its players—animal, plant, and human. And before I get any further, yes, we did hear the howl of the Mexican wolf, likely members of the Luna pack who’ve been displaying denning behavior for most of the spring.

Ocotillo are hallmarks of the Chihuahuan and Sonoran ecosystems. Their long, spindly fingers are easy to spot along the southern edge of the Greater Gila Bioregion and after a rain, bright red flowers emerge from the tips of the stalks.

Monday

On Monday, we attended a technical meeting hosted by the U.S. Forest Service in Silver City, N.M. The purpose of the meeting was to get public input on what types of monitoring the agency should include in its new Forest Plan. We heard many interesting and novel ideas about how to monitor the impacts of activities such as livestock grazing, logging, fire, and off-road vehicle use. A “hot topic” was how to measure the effects of climate change on the forest’s vegetation and native species. Unfortunately, the Forest Service hasn’t complied with its existing monitoring mandates, so we highlighted the need for the new Forest Plan to include increased rigor and accountability.

On Monday night heavy monsoon rains got the better of us and we retreated to a motel instead of camping. A few days later we were rewarded with fresh mountain lion and bear tracks in the mud created by Monday night’s storm.

Tuesday

The next morning, we again met with the Forest Service, this time about grazing permit retirement, logging and prescribed fire, and the possibility of partnering on stream and riparian area restoration projects. Pivoting the agency towards supporting the permanent retirement of grazing permits and minimal management of natural processes is a never-ending battle, so we rewarded ourselves with an afternoon on the banks of the Gila River.

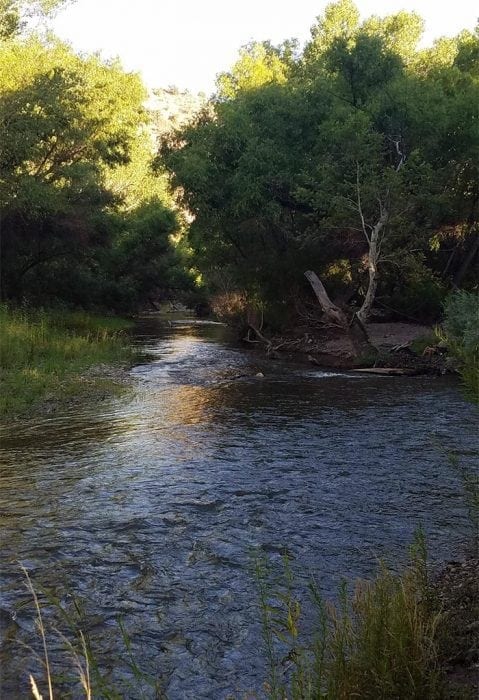

The Gila River flows for 641 miles from its origin high in the Gila Wilderness Area to its confluence with the Colorado River, and provides essential habitat for hundreds of species of fish, birds, amphibians, and wildlife, including endangered species such as Gila trout, loach minnow, Chiricahua leopard frog, and Southwestern willow flycatcher, as well as elk, deer, and javelina. But this lifeblood of the Gila National Forest, and of the entire Gila Bioregion, is currently under threat from a proposed large-scale diversion and storage structure for up to 14,000 acre/ft of water per year. It’s currently unknown what this diverted water would be used for. Guardians worked closely with our conservation allies to submit scoping comments opposing this project. It’s hard to imagine what this diversion would do to a river already feeling the impacts of drought and climate change.

At the Mogollon Box Campground, a few river miles below the proposed diversion site, the Gila was flowing with runoff from the previous evening’s downpour. Birds were abundant in the cottonwoods and other trees along the lush riparian area, and we basked in their songs in tune with the running water.

Wednesday

The following day, in Reserve, New Mexico, I introduced Judi and Sarah to my favorite diner and chocolate shop, the Adobe Cafe. We stopped in for a late lunch and, of course, dessert, and just happened to stumble upon a meeting organized by Senator Udall’s office and promoting small business development in the Greater Gila area.

As we drove on to our next campsite, we discussed the fact that the people at the meeting were interested in businesses related to recreation and tourism, not resource extraction such as logging and grazing. This is the future of economic development throughout the Greater Gila—as it is the economic future of all communities near federal public lands.

This transition is already happening here. Unfortunately, it’s threatened by the agency’s persistent favoritism of livestock grazing over all other uses, and ill-conceived projects such as the proposed diversion of the Gila River and an expansion of military training at Holloman Air Force Base, which will fly F-16s at low altitude over much of the Forest.

We even came up with a motto for our trip: “multiple use does not excuse abuse.” We heard repeatedly from the Forest Service personnel we spoke with about their multiple-use mandate that requires them to keep cows on the vast majority of federal lands. But as we traveled throughout the Gila, we witnessed heavily grazed lands devoid of vegetation, stripped to bare ground, where few birds or wildlife would choose to roam. Barbed-wire fences used to manage cattle crisscrossed the landscape in a never-ending barrier to wildlife migration. We witnessed an elk with a bad hind leg unable to jump a fence to travel with its herd and escape our human intrusion.

We spent our last night in the Gila camped up high in a ponderosa pine forest that was partly burned in this summer’s Buzzard Fire. We could see evidence of the earlier monsoon rains, and grasses and forbs were starting to green up the burnt landscape.

Wildfire is one of the most important natural processes within the Gila’s forested landscape. Unfortunately, active fire suppression and cattle grazing have limited fire’s natural flow, and the Forest Service is proposing to manage its way back to purported ecological stability through extensive logging and prescribed fires over the next 10 to 20 years. Yet despite the Forest Service’s claim that logging is necessary to preventing destruction by high intensity fires, most recent fires, including this year’s 50,000-acre Buzzard Fire, burned primarily at low- to moderate- and mixed-severity intensities. These fires provide huge benefits to the forests that evolved with exactly these types of natural disturbances.

Thursday

As we awoke under the pines on our last morning in the Gila, we were greeted by the yips and howls of Mexican wolves. They were close. They were so close we could almost see them. We tried, but had to be satisfied just to know that they were there.

We marveled at the remarkable resilience of this rugged, wild landscape, which endures even after more than a century of cattle grazing and mismanaged fire suppression, and even as a changing climate heightens each individual threat. For its sake, we continue to work on novel approaches to what was once an intractable problem.

More than 50 years ago, Aldo Leopold told the tale of the last grizzly in the Gila in an A Sand County Almanac essay titled “Escudilla.” Leopold, an employee of the Forest Service, famously changed his view of our role in forest management, carnivore species eradication, and wild ecosystems after daily experiences in the wilds of the Greater Gila. He writes:

We forest officers, who acquiesced in the extinguishment of the bear, knew a local rancher who had plowed up a dagger engraved with the name of one of Coronado’s captains. We spoke harshly of the Spaniards who, in their zeal for gold and converts, had needlessly extinguished the native Indians. It did not occur to us that we, too, were the captains of an invasion too sure of its own righteousness.

Escudilla still hangs on the horizon, but when you see it you no longer think of bear. It’s only a mountain now.

In 2018, the legacy of vanquishing wildlife, wildlands, and wild rivers is still in full effect, wreaking havoc on public lands and native species. What Leopold so eloquently articulated a half-century ago is still very much at play in the modern Gila. Our work to retire grazing permits, restore riparian areas, and allow natural processes to occur instead of active forest management come together in the Greater Gila to end agency over-management and the legacy of livestock grazing and instead to foster a stronghold for the return of healthy streams, native species, and natural processes.