To her fellow Guardians, she’s known as “Double Doctor Sam” (holder of two doctoral degrees in anthropology and law), avid Jazzercise instructor (she celebrated her 22nd anniversary in June), world traveler, and legal whiz.

But to the coal and oil and gas industries, she’s indefatigable and imperturbable, battering industry with suit after suit until Trump’s “energy dominance” agenda crumbles. Energized by her work to push the envelope—and the law—for the climate and our natural world, Guardians legal director Samantha Ruscavage-Barz is an indomitable force for nature.

Samantha at Tintagel Castle, set high on the rugged North Cornwall coast.

Digging deep

Born in a blighted Pennsylvania coal town, Ruscavage-Barz first fell in love with the Southwest through her professor’s slides in an “Archaeology of the Southwest” class at Penn State. She spent the next 17 years doing archaeology in the field. After earning her PhD at the University of Washington, she arrived in New Mexico to further her career.

Some of those years were exhilarating—like the two she spent painstakingly excavating several rooms in a 16th-century Pueblo site, Pueblo Blanco, in New Mexico’s Galisteo Basin. For the most part, however, Ruscavage-Barz conducted archaeological surveys for government development projects ranging from road-building to coal mining.

She was working at the New Mexico State Highway Department in the curiously titled position of “Highway Environmentalist” when fate intervened. Fittingly for this litigator-to-be, it came in the form of a lawsuit.

Ruscavage-Barz was overseeing the analyses of impacts to natural and cultural resources for a highway expansion project in southern New Mexico when a neighborhood group sued the Highway Department and Federal Highway Administration over the project, arguing that their analyses did not adequately capture the historic character of the farming communities, acequias, and houses that would be damaged for the sake of two extra lanes.

The suit didn’t faze the Highway Department, but it did rattle Ruscavage-Barz.

“The people living in the path of the highway expansion voiced concern that the road was going to completely change the character of their communities. The Highway Department just wanted to bulldoze past their concerns and dismiss them,” she said.

As she witnessed the communities’ lawyers fight for their right to exist, she also found herself impressed with the power of the law.

Lawyers, she realized, “give people and nature—who don’t normally have a voice in project planning—a seat at the table as decision-makers.”

She spoke to the lawyers and investigated the laws intended to protect the environment and cultural resources, unearthing a system of natural and cultural protections that development agencies were prepared to ignore unless they were held accountable by conservation-minded lawyers.

“Among development agencies, the focus is on consumption of natural resources and their income-generating potential,” she said. “I saw the need for voices to protect natural resources for their own sake.”

Determined to give voice to the voiceless, she quit her job at the Highway Department and enrolled at the University of New Mexico School of Law.

Samantha at Bandelier National Monument in New Mexico.

Learning to lose

Ruscavage-Barz became WildEarth Guardians’ climate and energy staff attorney in 2010. Rather than a timeline of legal triumph, her next five years at the organization would be a lesson in loss.

It wasn’t until 2015 that she won her first case, which derailed coal mining expansion schemes in Colorado, Montana, and New Mexico.

She admits that half a decade of losing was “disheartening,” but also takes pride in her—and Guardians’—persistence, likening it to the fight for equality during the Civil Rights era. Brown v. Board of Education was by no means the first case the NAACP filed against segregation in public schools, but it was the one that stuck, and the one that shattered the status quo forever—just as one of WildEarth Guardians’ coal mining cases invoking the need to consider climate finally set the stage for safeguarding our climate.

The fact that Guardians encouraged her to continue to bring cutting-edge cases over those five years, even if that often meant losing, “kept me going,” Ruscavage-Barz said.

Her persistence has paid off in the years since that first win. One by one, judges are siding with Guardians and holding the government accountable to our climate and our planet—resulting in billions of tons of coal kept in the ground, reconsideration of decisions to sell nearly four million acres of oil and gas leases in Wyoming, Utah, Colorado, Montana, and New Mexico, and plans to drill more than 4,000 fracking wells in Greater Chaco curtailed.

No longer does Ruscavage-Barz excavate the remnants of ancient civilizations. Instead her job now involves construction—painstakingly assembling proactive protections for the Wild, communities, and the environment from the ground up, each successive case building on its predecessor until robust environmental protections and government accountability emerge from the detritus of climate denial, coal mines, and fracking pads.

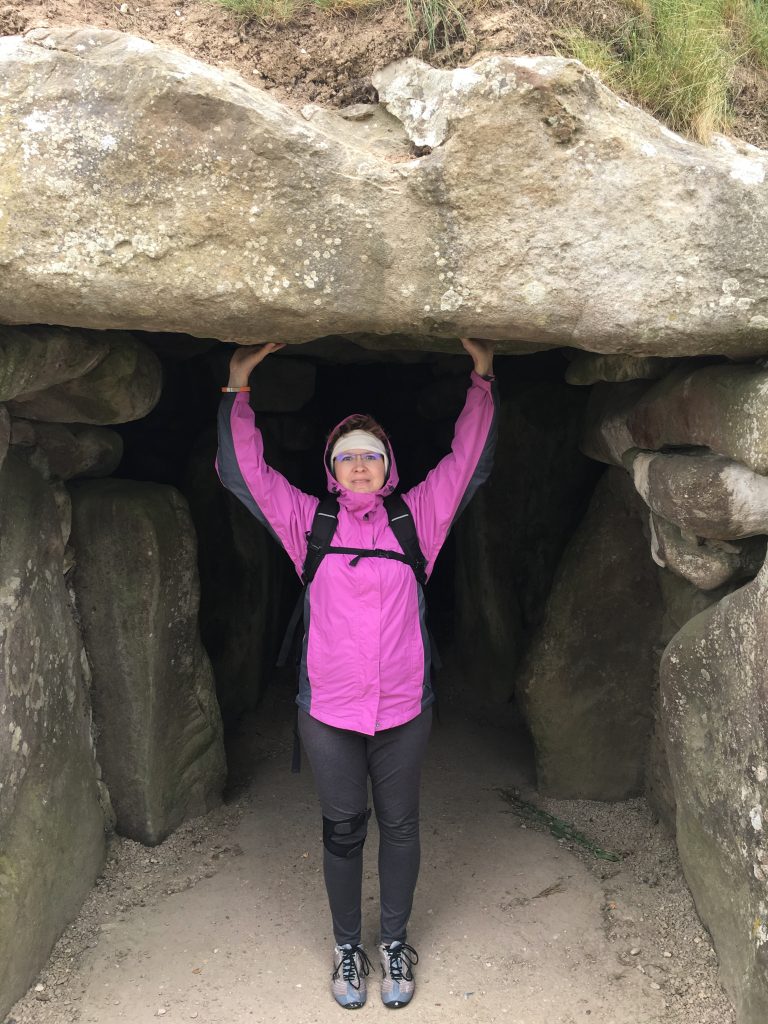

WildEarth Guardians’ rock solid legal director “Double Doctor Sam” exploring Avebury Henge in southwest England.

12 years on

Ruscavage-Barz has been a Guardian for nearly a third of the organization’s existence. But even as Guardians expands, she notes, the legal strategies that have defined it over the past 33 years continue to be effective in protecting our environment and holding government accountable.

“Guardians’ legal work has always been prudent, but pioneering,” she said. “We don’t bring litigation without thinking it through. But at the same time, we don’t hesitate to go where no one has gone before.”

As threats to our wild places, wildlife, and climate grow ever more perilous, and as courts increasingly heed Guardians’ calls for change, one thing remains plain: we’re lucky to have Ruscavage-Barz in our corner.

Like what you just read? Sign up for our E-news. Want to do more? Visit our Action Center.