The small crew of women met in the parking lot of Rocky Flats National Wildlife Refuge at 9:00 AM sharp. They were armed with gloves, buckets, and trowels. Their mission: removing invasive plants from a newly established prairie dog colony.

The crew consisted of Lindsey Sterling-Krank and Jenny Bryant from the Prairie Dog Coalition; their volunteer Hannah Reeves; Pam Wanek, a prairie dog relocator; and Taylor Jones with WildEarth Guardians. The prairie dogs were recent transplants from a construction site in Parker, Colorado. The newly established colony was thriving; pups were up and about, and sentries chirped warning calls at the approach of humans. But the prairie dogs still needed a little help transforming their section of Rocky Flats back to healthy native prairie. And the crew was here to provide that help.

Dalmatian toadflax is very pretty, with yellow flowers resembling snapdragons. It was imported from Eurasia for its looks—then it went wild. It is one of the many nonnative plants crowding out natives in grasslands hammered by livestock grazing and other human uses.

The best way to get rid of Dalmation toadflax is simple hand-weeding. The crew waited until after a spring rain, and then quickly sprang into action to remove the weeds before they went to seed and spread. Removing this invasive plant makes room for native plants and flowers, restoring the grassland to its natural state.

Prairie dogs are a keystone species of the grassland—they trim vegetation, providing habitat patches for flowering plants and ground-nesting birds like mountain plovers. They turn the soil, increase water absorption, and redistribute nutrients. Their burrows are home to many other species including burrowing owls, snakes, salamanders, rabbits, and insects. And as a prey species, they provide sustenance to a wide variety of animals including black-footed ferrets, coyotes, badgers, swift foxes, bald and golden eagles, and ferruginous hawks.

But sadly, there are few places left where prairie dogs truly fulfill their keystone role. Human-caused threats stemming from crop agriculture, livestock grazing, energy development, residential and commercial development, prairie dog shooting, poisoning campaigns, and plague (an introduced disease) have caused the five species of prairie dogs to disappear from an estimated 87 to 99 percent of their historic range, depending on the species. With them went the black-footed ferret, now one of the most endangered animals in North America.

Restoring prairie dogs to their keystone role is a long-standing goal of both Prairie Dog Coalition and WildEarth Guardians, though the two groups work toward that goal in different ways. WildEarth Guardians has focused mainly on policy and law. The group tried for many years to get black-tailed prairie dogs listed under the Endangered Species Act. They also analyzed and graded state policies regarding prairie dogs for a decade. Prairie Dog Coalition’s main focus has been relocation of prairie dogs away from sites where they are in danger of being poisoned or bulldozed to protected sites like wildlife refuges or national grasslands. The two groups recently came together to create a guidance document for communities interested in implementing humane prairie dog management plans. Since most species of prairie dog are not protected under federal or state law, cities, towns, and municipalities can play an important role in prairie dog conservation and avoid unnecessary killing of prairie dogs by including prairie dogs in their planning processes. Good planning facilitates relocation projects like the one that saved the prairie dogs now thriving on Rocky Flats.

The project was a success—the crew removed a truckload of Dalmation toadflax. Weeding the vast expanse of prairie by hand may seem like a daunting task, but every bit of work is a step closer to a healthy, whole native grassland. With the prairie dogs keeping vigil behind them, the crew left at the end of the day with the satisfaction of knowing they’d made a tangible difference, even just for a small patch of prairie. Sometimes you have to be like a prairie dog; pick your small patch of ground, nurture and defend it, and know that together, you make up a great ecosystem of helping hands making it easier for nature to heal itself.

The entrance to the prairie dog relocation site on Rocky Flats National Wildlife Refuge. Photo by Taylor Jones, WildEarth Guardians.

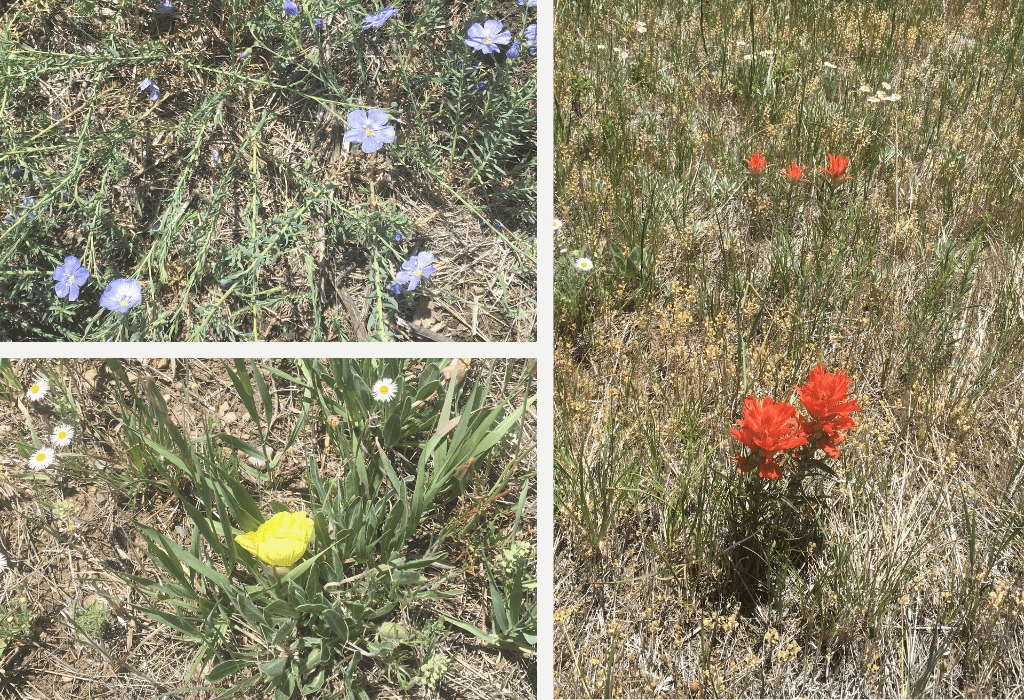

A few examples of the subtle beauty of prairie wildflowers. Photo by Taylor Jones, WildEarth Guardians.

This baby rattlesnake is just one of the many animals that call the prairie dog colony home. Photo by Pam Wanek.

Dalmatian toadflax, the invasive Eurasian plant we were focused on removing. Photo by Taylor Jones, WildEarth Guardians.

Lindsey Sterling-Krank of the Prairie Dog Coalition with a truck full of invasive Dalmatian toadflax. Note the COVID-19 safety procedures in place. Photo by Jenny Bryant.