Current work in wildlife, rivers, public lands, and climate

Press Releases

Rio Grande Basin forecast suggests another difficult water year ahead

“It’s déjà vu in the Rio Grande Basin as we stare down another hard water year with every drop of water and then some promised to somebody. It’s never been clearer that we need to drastically rethink how we value and manage Western waterways,” said Tricia Snyder, Rio Grande Campaigner for WildEarth Guardians.

A drying Rio Grande pictured in Las Cruces, New Mexico in September 2021. Photo by Javier Gallegos.

In the Upper Rio Grande Basin, 75% of streamflow originates from snowpack. But snow in the mountains doesn’t necessarily translate to water in the river come spring. A recent study confirmed that the past two decades in the American Southwest have been the driest in at least 1,200 years and our understanding of the role warmer temperatures play in aridification, or a more permanent drying of the region. Dry conditions translate into parched soil, which means more snowpack is needed to reach even an average amount of runoff.

Another important piece of the puzzle is the timing of that runoff. The snow that falls in the winter serves as a natural reservoir for the Basin, holding onto water until spring when warmer temperatures begin to melt it. This spring runoff is particularly critical for ecosystem needs and for the health of imperiled species. But earlier this month, the US Geological Survey (USGS) released a new study highlighting the precipitation regime shifts that climate change is causing in the Basin. The study suggests that peak runoff could arrive as much as a month earlier than the historic average, with much of the Basin’s precipitation falling as rain rather than snow by the end of the century.

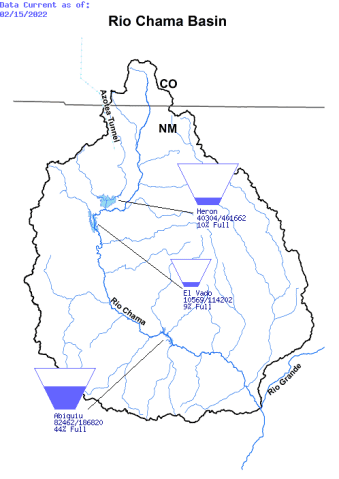

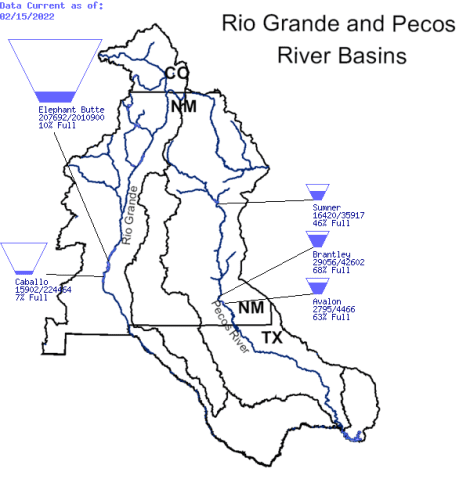

Similarly to 2021, the reservoirs on the Rio Grande and Rio Chama (e.g. Heron, El Vado, Abiquiu, Elephant Butte, and Caballo) hold a mere fraction of their capacity in water. This lack of water in storage means that the reservoirs will not be of much help when stream flows inevitably dwindle over the summer. Currently the reservoirs hold a total of 355,587 acre-feet (116 billion gallons), an uptick from this time last year when they held 324,985 acre-feet (106 billion gallons) but a mere 12% of the reservoirs’ capacities. An acre-foot is the amount of water it takes to cover a football field in one foot of water and is enough to supply water to a family of four for one year.

“Our water challenges aren’t going away,” added Snyder. “In fact, each dry year those effects are compounded. We must act now to ensure we don’t do permanent damage to the ecosystem and the quality of life a Living Rio provides.”

BELOW: The U.S. Bureau of Reclamation’s River Basin Teacup Diagrams show the current storage for reservoirs on the Rio Chama and Rio Grande. See: https://www.usbr.gov/uc/water/basin/index.html