I walked across the crusty remains of the once-mighty Rio Grande and felt completely devoid of hope. As I stood in the center of the river in the heart of Bosque del Apache National Wildlife Refuge, there was not a glimmer of water in sight. As defeating as it is to see a disappearing river in which only a tiny ribbon of water remains, it is even more devastating to stand in the sand where chocolate-colored water used to flow.

Sadly, a dry Rio Grande between Cochiti Dam and Elephant Butte Reservoir—the reach referred to as the Middle Rio Grande—is not an uncommon sight. Since 1996, the Rio Grande south of Albuquerque, New Mexico, has dried every year. While in 2008 only three miles of the river dried, in 1996 about 90 miles dried. The difference in forecasted flows in those years were 155 percent of average in 2008 and 34 percent in 1996.

To put this amount of drying in perspective, there are 174 miles in the Middle Rio Grande. So when 90 miles dry, more than half of the length of the river is dry. Such vast drying has significant harmful effects on the riparian vegetation, aquatic habitat, and the fish and wildlife that call the river home.

I got to experience this harm firsthand in September of 2016. The day after I stood in the completely desiccated riverbed of the Rio Grande, I accompanied two U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service biologists on their summer ritual to “salvage” critically imperiled Rio Grande silvery minnows—a small species of fish protected under the Endangered Species Act—from isolated pools as the Rio Grande dried. As the river’s flows receded due to agricultural diversions upstream, we took to ATVs and blasted up the dusty channel of the river looking for any remaining pools of water where fish might be found.

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service biologists seining the Rio Grande for silvery minnows in September of 2016. Photo by Jen Pelz.

We found catfish and red shiners and silvery minnows fighting for their lives in murky brown ponds of water among the vast sea of sand. What stuck with me about this journey was not the joy of saving a select few endangered silvery minnow from certain death, but rather turning our backs on hundreds of other fish that would also certainly perish.

Tiny catfish found in a footprint of water along drying Rio Grande near Los Lunas, New Mexico. Photo by Jen Pelz.

It was this same sense of outrage that I felt in 2016 that sparked Guardians’ activism to protect and restore flows in the Rio Grande more than 20 years ago. In 1996, the Middle Rio Grande Conservancy District, the local irrigation district, diverted the entire flow of the river in April (despite abysmal flows of less than 34 percent of average), drying the river and killing tens of thousands of (at the time) newly listed endangered silvery minnows. Since that time, we have been using all the tools available to fight for the river’s right to its own water and to take down the institution and policies that seek to kill it.

Just to be clear, the Rio Grande is a perennial river—meaning it flowed year-round—at least before humans began diverting and controlling its flows in an unsustainable manner in the mid-1800s. This was true even during dry periods. Unfortunately, the river’s needs were never considered when its waters were allocated to farms and cities.

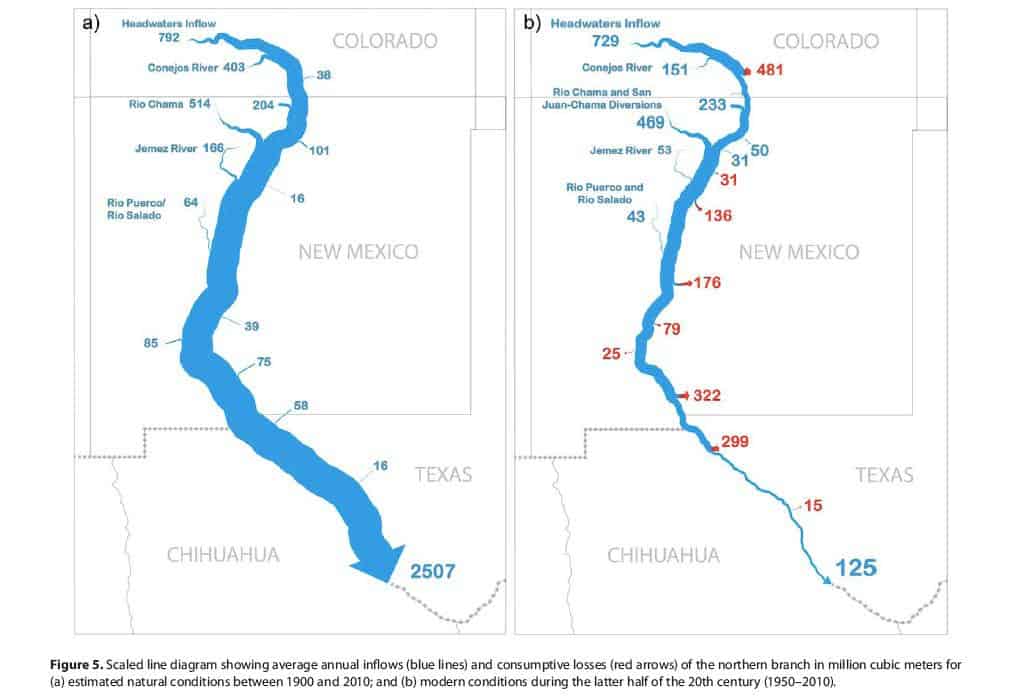

In a recent study, Estimating the Natural Flow Regime of Rivers with Long-Standing Development: The Northern Branch of the Rio Grande, Todd L. Blythe and John C. Schmidt recreated the historic flow regime of the Rio Grande using gauge data from the U.S. Geologic Survey. This effort resulted in the following line diagrams showing the average annual inflows in blue and consumption losses in red.

As indicated by the maps, the Rio Grande once did deserve its name, but is now so severely depleted by human uses that it is used up before it reaches El Paso.

This year could be the worst year on record. The forecasted flows are 20 percent of average—no forecast in the past 20 years has been that low. As of June 30, 2018, 27 miles of the river have already dried and over 100 more miles could dry before October. Until the Rio Grande receives a right to its water, the river will be at the mercy of the unsustainable water use and management along the way.

The impending crisis, while bringing fear and uncertainty to all who depend on the river—from the bobcat and black bears that use the river as an important wildlife corridor to the communities that need it for their livelihoods and quality of life—also brings great opportunity.

In the last month, the plight of the Rio Grande was featured on the front pages of the New York Times and Denver Post. In addition, the river is lucky to receive consistent and in depth coverage from our local reporter, Laura Paskus, of the New Mexico Political Report. The silver lining of the crisis is that the issues plaguing the Rio Grande—including the struggle to reconcile ancient water law and policy with the changing climatic conditions and the challenge of preserving flows in our iconic river—are being exposed.

We can chart a new course for the Rio Grande. It will not be without difficult decisions, likely conflict, and some significant institutional changes, but it is possible. We need your help to keep the pressure on and turn this crisis into opportunity. Here is what you can do:

- Visit the Rio Grande with your family, friends, and neighbors to experience its beauty and foster community.

- Share your stories, photos, and love of the river with your community, your senators, and your representatives and ask them to ensure that the Rio Grande’s flows are protected for future generations.

- Take a photo of the Rio Grande, tag us @wildriversguardian, use hashtag #rethinkrivers and we will repost. Share your experience and let us shine a bright light on what is happening to our iconic Rio Grande.