I love maps. For most people, maps are just flat pieces of paper, but not for me. Even as a kid, when I looked at the contours on a map, I understood the lay of the land—and what it meant. I could see the peaks and the valleys and even imagine what kind of trees and flowers grew there. If I look at a map, I can see the land before I even get there. Looking at maps has made me do a lot of things. Like hike 36 miles in a day, scamper off trail in search of ancient cliff dwellings and, mostly, imagine beautiful places not yet seen.

Usually I get a map before I go on a journey, when I already know the destination. The destination is always some place beautiful. But recently, I saw a map that started a journey before I knew the destination. A map to a place of darkness.

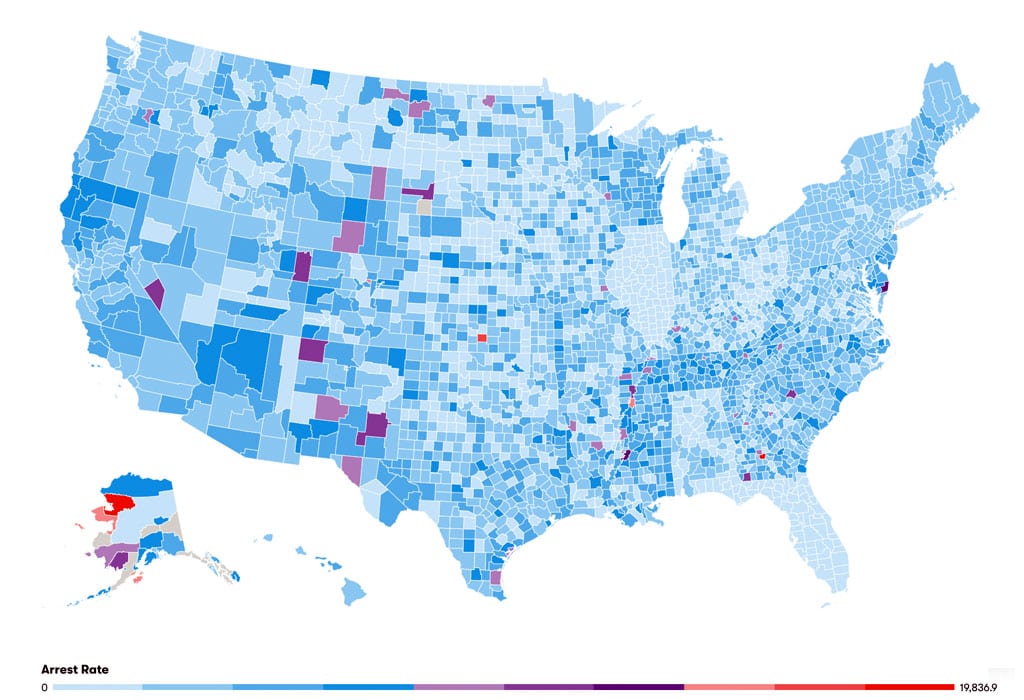

The map, created by the Vera Institute, a non-profit that exists to reform our criminal justice system,[1] shows incarceration rates in every county in the U.S. It highlighted the “hot spots” where incarceration rates are highest. Looking at this map I had a strong feeling of déjà vu. I had seen this map before. The incarceration map could easily have been a map of the coal, oil and gas reserves in the American West. It’s almost a perfect overlay. The hot spot counties for incarceration in the West match areas with high concentrations of fossil fuel extraction.

I knew that ground zero in our nation’s opioid epidemic are the coal fields of West Virginia. Then I recalled a conversation with Jeremy Nichols, our Climate and Energy program director. He told me that one of the West’s oldest coal mining regions—Carbon County, Utah—also has one of the highest rates of opioid addiction in our nation.[2]

Could we add a third leg to this triangle of injustice?

The answer is: Yes.

The highest rates of opioid addiction in the American West are in fossil fuel country. And the highest incarceration rates are in fossil fuel country.

It’s no coincidence that high incarceration rates sync with fossil fuel hot spots. Just like the oil and gas industry, private prisons are big business in America. You don’t dig for coal in Central Park. You don’t build a private prison in Beverly Hills.

Of course, these maps aren’t just data points; they’re stories of people’s lives.

In Dearborn County, Indiana, an individual by the name of Donnie Gaddis sold 15 oxycodone pills to an undercover officer. He was sentenced to 12 years in prison. If Donnie had been caught twenty miles to the east, in Cincinnati, he would have gotten six months. If he had been arrested in San Francisco or Brooklyn, he would have been sentenced to a drug treatment program.[3] But those places are more affluent than Dearborn, Indiana, where civic leaders made the cruel choice of investing in prisons instead of people.

Guess which states have the highest percentage of inmates in private prisons in the entire United States. New Mexico and Montana. And two of the other top ten are Wyoming and Colorado.[4]

There’s an old saying in real estate that location is everything. The same can be said of environmental and human justice. The common factor in each of these places, in each of these hot spots, is poverty. The most obvious definition of poverty is the absence of money, but more fundamentally it’s the absence of power.

People who lack power are, by definition, vulnerable. One of the sad facts of human history is that the powerful will always find a way to make a buck by exploiting the vulnerable. And just like predators in the wild, economic predators know where to find their prey.

Right here on the Front Range of Colorado that struggle between the oil and gas industry’s predatory instincts and its prey communities is playing out. In 2013, a power company was given permission to drill a few hundred feet away from Frontier Academy—a prestigious, mostly white charter school in Greeley. As you’d probably guess, the parents and neighborhood residents were outraged, and the project was put on hold. In 2016, another power company was approved for a new site—a few hundred feet from the Bella Romero Academy, where the majority of students are Latino, and the children of immigrants and refugees.[5]

This is the perfect geometric proof about how to save the environment. The environment is safest in places where people have power. Environmental issues and poverty issues aren’t linked in some sort of ethereal or metaphorical way, but in a real, concrete, political—and geographic—way. As long as there are vulnerable communities to exploit, for either their natural or human resources, there will be powerful forces to exploit them.

If we only focus on the environmental issues of a community, we are missing more than half the picture. At WildEarth Guardians, we’re changing our way of thinking. Instead of trying to get the little guy to be on our side, we have to recognize that standing up for the little person, empowering those who are vulnerable, is vital to protecting the environment.

Aldo Leopold wrote: “We abuse the land because we regard it as a commodity belonging to us.”

Economic inequality and environmental catastrophe aren’t separate issues; they are symptoms of the same disease. Namely, a mindset that views people and places and animals as commodities to be exploited. The incarceration map, the addiction map and the fossil fuel maps are nothing less than maps of exploitation. Exploitation of the most vulnerable.

More than anything, a Guardian is a defender of the vulnerable. For the last 30 years WildEarth Guardians has been fighting to protect the vulnerable, whether that’s endangered species, threatened wildlands, or imperiled rivers. And our climate. Most recently, in April, we won a lawsuit blocking the sale of coal taken from public lands.[6] And in March, we won a groundbreaking lawsuit that could protect millions of acres of public land from the oil and gas industry.[7] Because of our work, the Department of Interior will have to make new maps.

But we have to change even more maps. We have to do our level best to eliminate as many “hot spots” of exploitation as we can.

For far too long environmental interests have been portrayed as opposed to economic interests.

We have to make it our mission, in word and deed, to live the truth that economic interests and environmental interests are one and the same. We need to do this because the natural world we love so dearly will be safer, by leaps and bounds, in a world where everyone has the economic power necessary to defend their communities from the nefarious forces that would exploit them.

WildEarth Guardians’ work for the next 30 years is to imagine new maps.

- New maps… that end the extraction and exploitation of our public lands and shift our economies to a new paradigm that is restorative and regenerative.

- New maps… that create corridors to connect the great wildlands of the American West—from the Greater Gila to Rocky Mountain National Park to Greater Glacier along the Spine of the Continent.

- New maps… that give wolves and other native carnivores the freedom to roam.

I need your help and the help of other Guardians—young and old, black and white, urban and rural—to make these maps a reality. Our very survival depends on it.

[1] https://arresttrends.vera.org/arrests?type=county&unit=rate&year=2014#map

[2] https://le.utah.gov/interim/2018/pdf/00003613.pdf

[3] https://www.nytimes.com/2016/09/02/upshot/new-geography-of-prisons.html

[4] https://www.axios.com/the-states-where-private-prisons-are-thriving-1513306984-8e4d9dc6-8bd2-4ea8-93dc-47a187977bca.html

[5] https://www.sierraclub.org/colorado/blog/2019/02/bella-romero-academy-and-fight-against-fracking

[6] https://www.nytimes.com/2019/04/19/climate/court-trump-coal-mining-setback.html

[7] https://wildearthguardians.org/press-releases/landmark-climate-victory-federal-court-rejects-sale-of-public-lands-for-fracking/