Current work in wildlife, rivers, public lands, and climate

Press Releases

Troubling 2021 outlook for the Rio Grande Basin

“We’re facing an incredibly tough water year for both people and the environment,” said Tricia Snyder, Rio Grande Campaigner at WildEarth Guardians. “As climate change continues to ravage the West and expose the region’s unsustainable water use and archaic policies, it’s an urgent reminder that we need a drastic overhaul in how we value and manage western rivers.”

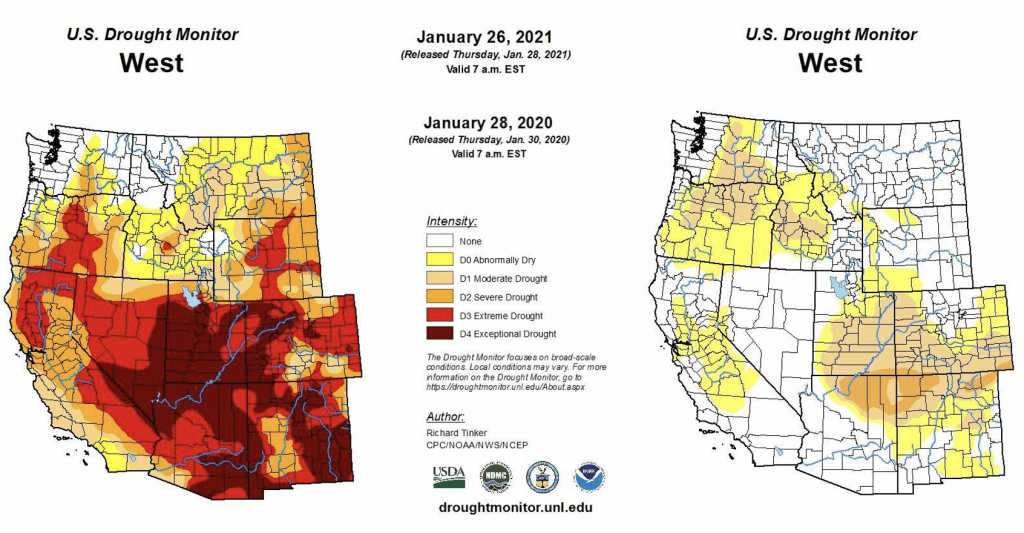

The U.S. Drought Monitor identifies most of the West as being in extreme or exceptional drought conditions. New Mexico is experiencing severe drought conditions with over 54 percent of the state identified as being in exceptional drought.

U.S. Drought Monitor’s West Drought Summary as of January 26, 2021 (on left) and January 28, 2020 (on right). See: https://droughtmonitor.unl.edu/

This is a stark change from the conditions on the ground last year. In 2020, conditions were abnormally dry and parts of the West were experiencing moderate to severe drought, but nothing like this year.

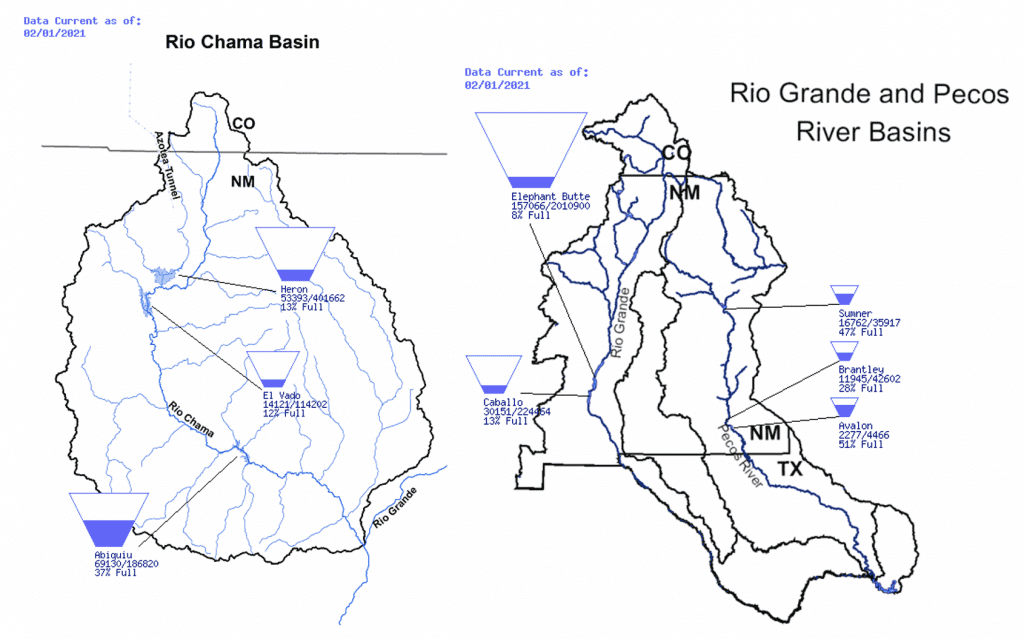

Another significant difference this year is that reservoirs on the Rio Grande and Rio Chama (e.g. Heron, El Vado, Abiquiu, Elephant Butte, and Caballo) are just at a fraction of their capacity which means that water in storage will not serve to buffer these extremely dry conditions and less than average flows.

The U.S. Bureau of Reclamation’s River Basin Teacup Diagrams show the current storage for reservoirs on the Rio Chama and Rio Grande. See: https://www.usbr.gov/uc/water/basin/index.html.

Currently only a total 324,985 acre-feet (106 billion gallons) of water total is stored in these five reservoirs, compared to the 857,700 acre-feet (279 billion gallons) of water stored at the start of last year. An acre-foot is the amount of water it takes to cover a football field in one foot of water and is enough to supply water to a family of four for one year.

“In a basin where every drop of water is already promised to water users and the river does not have right to its own water, we have to take these changes to flow regime shifts very seriously,” added Snyder. “Let’s not turn a blind eye to the permanent consequences of species extinction and ecosystem collapse that will result if we don’t provide basic flows to the river’s living things.”

To complicate matters further, the application of rigid and archaic laws and agreements—like the Rio Grande Compact—that serve to allocate water between Rio Grande Basin states will have severe consequences on how and where water is available. For example, a 2013 Reclamation study concluded that due to climate change flows in the Rio Grande will decrease overall by about one-third by 2100. However, these impacts will not be felt uniformly across the Basin. Flow declines are projected to be 25 percent in Colorado, 35 percent in the middle valley in central New Mexico, and up to 50 percent in southern New Mexico and Texas.

Further, New Mexico currently owes Texas nearly 100,000 acre-feet of water. As a result, New Mexico water users will have to bypass water through reservoirs where it could typically be stored. It also means there is a lot of pressure on water managers to bypass river ecosystems (by routing the river’s water through canals, drains, and other artificial channels) to fast track it to Elephant Butte Reservoir to deliver to Texas and meet compact obligations. The use of artificial channels left the Rio Grande dry late into November of last year and this could happen again and often in 2021.

“This year is going to require hard choices and sacrifices if we have any chance of maintaining the irreplaceable Rio Grande ecosystem and the quality of life New Mexicans have come to know,” said Jen Pelz. “My hope is that compliance with an 80-year old agreement does not dictate the care we bring to ensuring that water is shared and the basic needs of the environment are not sacrificed.”

Rio Grande at Bosque del Apache National Wildlife Refuge. Photo credit: Jen Pelz.

WildEarth Guardians (www.wildearthguardians.org) is a conservation non-profit whose mission is to protect and restore the wildlife, wild places, wild rivers, and health of the American West. Guardians has offices in Arizona, Colorado, Idaho, Montana, New Mexico, Oregon, and Washington, and over 275,000 members and supporters worldwide. Follow Guardians on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram for updates.

Rio Grande Waterkeeper is a program within WildEarth Guardians that works to safeguard clean water and healthy flows in the Rio Grande from its headwaters in the San Juan Mountains of Colorado through Southern New Mexico. The program was formed out of a partnership between Guardians and Waterkeeper Alliance, a global movement united more than 300 Waterkeeper Organizations and Affiliates around the world. Follow Rio Grande Waterkeeper on Facebook.