I delight every time I cross into Wilderness. Though it’s a line defined on maps, posted on trees or other signposts, and wrestled with time and again by corporations and conservationists, it’s also my opportunity to transcend the world of progress—of people.

Physically crossing into wilderness is only half the battle—the more obvious one, typically involving more steps from the trailhead. The harder passage is the one separating humanness from wildness, a state of being I call “wild time.” My 6-year-old daughter also has a definition of “wild time,” one that is probably even more primal and accurate than mine, yet we are both in agreement that in wild time, there’s more emotion, heart, and aliveness—and possibly a lack of sleep, too.

Today was the first time in months that I was able to cross the threshold into wild time.

Crossing the physical boundary is only half the battle.

The wind that often dominates Colorado’s high and dry San Luis valley had abated at the lower elevations and the cold front had moved east, leaving clear skies and a few inches of dry snow on the hillsides. Even though the sun was low and quick across the sky, the rabbit brush-, prickly pear-, and grass-filled south- and east-facing slopes lost their sparkle within minutes.

The air on the 45-minute hike to the fallen fir tree that signaled the designated transition to the wilderness was sharp, cold, and dry in my throat. The areas of the trail that had snow were quiet, allowing me to more easily slip undetected into the wild. I followed a steadily rising, yet gracefully contouring game trail up to the rocky, piñon- and Douglas fir-filled ridge above the aspen-lined, grassy creek bottom. I followed fox tracks, then a few deer tracks, while listening to the woodpeckers pecking away. When I stopped moving, they created the only sounds breaking the crystalline stillness.

A discreet pathway.

I’m curious about what “everyone” is doing in their wild world and snow helps to paint a picture of those events, where even the small things that I would normally not be privy to, like birds poking around in the snow for food, are ephemerally etched into the landscape. I was just a visitor and, from my perspective, the day was peaceful, warm, and lovely on this sunny sub-ridge of the giant valley. But spindrift casting a long tail off the mountain 4,000 feet higher indicated that my perspective was, as always, limited.

Further up the ridge, I crossed a single set of elk tracks. It’s typical for a lone bull to hang up here after the rut, after hunting pressure has pushed him away from his preferred habitation zone, leading him to eke out a living in a small ecological zone with just enough dried grasses and forbs for him alone. If he’s lucky enough to recuperate from rutting battles and build up his depleted fat reserves for a cold winter on this lean diet, he’ll follow the “green up” next spring to a more fertile forest, shed his antlers once again and prepare for the next breeding cycle. I walked his path, my footprints dwarfing his more demure and delicate five-inch-long, split-toed hooves. I found his bed, an oval of snow thawed and refrozen from his mass and heat. Leaving this solitary bedroom, his tracks indicated a relaxed pace—it wasn’t me who roused him.

My “goal” for the day was a grassy, sunny saddle with a tremendous view of the valley and the rugged, snow-capped peaks. There, I took a seat under the lone gnarled Doug fir, on a patch of dirt worn in the grass by eons of ungulates who have made a bed there. I chose to ruminate on wildness and wilderness rather than a breakfast of crunchy grasses and freeze-dried forbs.

Sunny, windy and dry, integral qualities of this lonely wild range.

The sun crept along the sky. My comfortable ruminating spot now shaded, cold begged me to make a change and I continued on. I headed down the steep, dry, and grassy hillside past a handful of past-prime puffballs—the western giants that make awesome “steaks”—and a few tansy asters holding onto this year’s purple. The transition back to riparian was highlighted by the crisp line of shady snow.

Giant puffballs give gastronomic delight picked prime.

The snow revealed a great number of deer tracks, deer beds, chomped blonde grass, and other, more base-level daily remnants of ruminants. Taking their lead down to a seep spring lined with bittercress and green grass, I stopped to quench my thirst as those who preceded me had done today. That bathtub-sized spring, a tiny oasis of vibrancy, life, and activity in a mostly desiccated landscape, reminded me that all animals who make the West their home are tethered by the same needs.

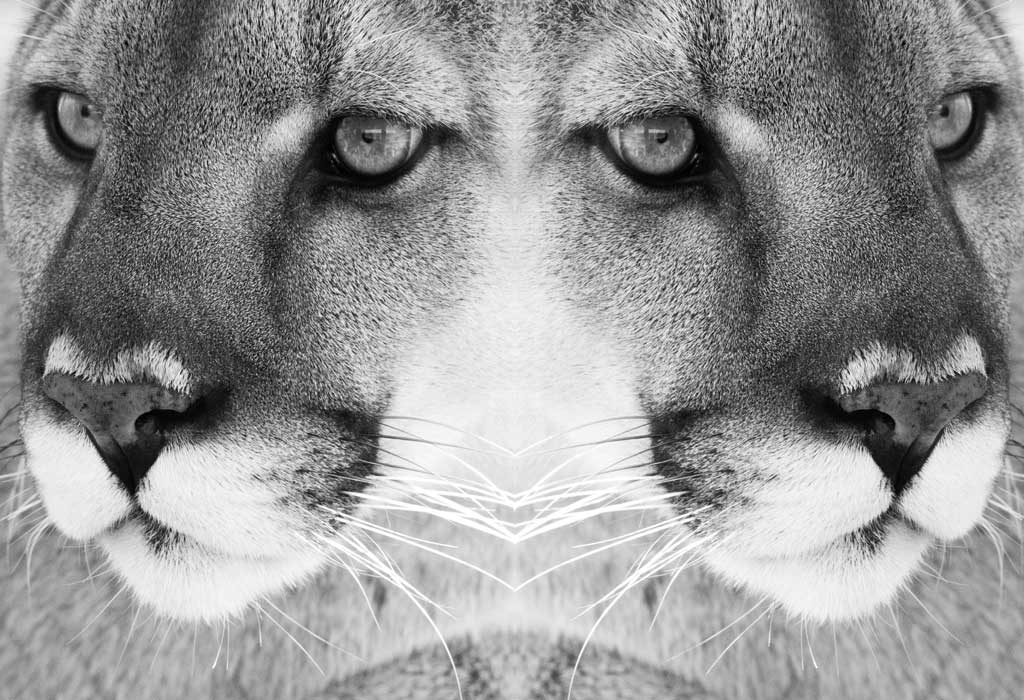

Further down the snowy drainage, nearly hand-sized paw prints indicated an animal looking for something other than herbaceous sustenance. Only occasionally did the lion’s claws penetrate the snow, yet each of those paw prints pierced my psyche.

Occasionally, even carnivores need to get a grip.

I’ve been fortunate enough to experience the presence of a lion at intimate distances in the Wilderness a few times. With awe comes respect, as the lion has likely eyed me a thousand times over. After literally jumping up and down like a sports fan when I ran into that carnivore’s tracks—the wild in action!—I investigated the morning’s story further.

Paying homage to past paths.

That morning the lion went hungry, at least from what I could tell, but my hunger to be awed by the wild was well-fed. The sun was low in the Western sky, turning the snow a grayish hue of blue. For me, it was getting hard to see; for others, wild time was about to start…again.