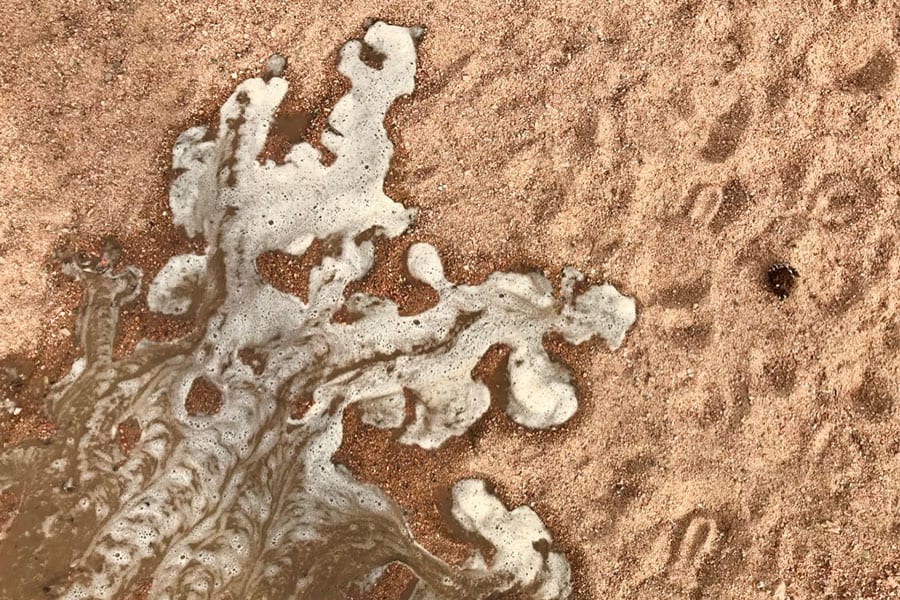

Roaring through the late summer air comes an unfamiliar sound—the sound of earth moving, of revitalization, the sound of water. Arroyo Chamiso, just 100 yards from my home, is usually a braided bed of sand, cactus, and shrubs, connecting our neighborhood to the land. Chamisa brush, piñon and ponderosa pines, juniper, cottonwood, and cholla line the sandy wash, a neighborhood haven for wildlife.

The smell that emanates after an arroyo floods is one of crisp botanical reverie, the smell of rain on dust, of plants rejoicing. The cycle of dry and wet is embedded in this landscape far beyond human memory; it is part of the life of this place.

During monsoon floods, the sound draws neighbors to watch as Arroyo Chamiso becomes a raging torrent of sedimented waters, seething over Fort Union and Conejo Drive, carrying thousands of tons of sand and clay, rock, brush, and debris out of the foothills toward the Rio Grande.

I recall learning in school, to my surprise, that arroyo in Spanish means “stream.” In New Mexico, arroyo means something different; a sandy wash that is there by and for floods and occasional spring runoff. The phenomenon of arroyos flooding into intense rivers is one that all New Mexicans can identify with. Arroyos are veins of the high mountain desert—our streams a few times a year flood with life.

Right now, the Trump administration is working towards a sinister rollback of existing clean water protections for intermittent and ephemeral streams. The proposed rule attempts to redefine which streams, rivers, lakes, and wetlands are protected by the Clean Water Act. Under the proposed rule, all of New Mexico’s creeks, arroyos and washes that only flow in response to precipitation, over 90% of the state’s waterways, would lose protection.

The proposed rule is designed to benefit polluting industries and prevent communities from using the Act and the courts to protect the quality of their water. This is a blatant transgression of our right to clean water.

If arroyos are made open dumping grounds for agricultural or industrial waste, contaminants will eventually end up in groundwater, the Rio Grande, and coming out of our taps. Imagine a flash flood of mining sludge, fracking fluid, or raw manure. This poses a threat to millions of people, our children, grandchildren, and great-grandchildren.

These days, when I go out in Arroyo Chamiso’s winding channels, I can’t help but feel that the proposed waters of the United States rule is an affront to my personal health. Clean water is a right, and to preserve it we must enforce regulations and hold industry accountable for keeping our waters clean, safe, and healthy.

Today is the last day to comment on Trump’s dirty water rule, find out how here.